Shamans, sun gods, warriors: Thousands of Bronze Age petroglyphs mark this ancient site

In Kazakhstan’s Tamgaly gorge, 3,500-year-old rock art provides clues about the society that created them.

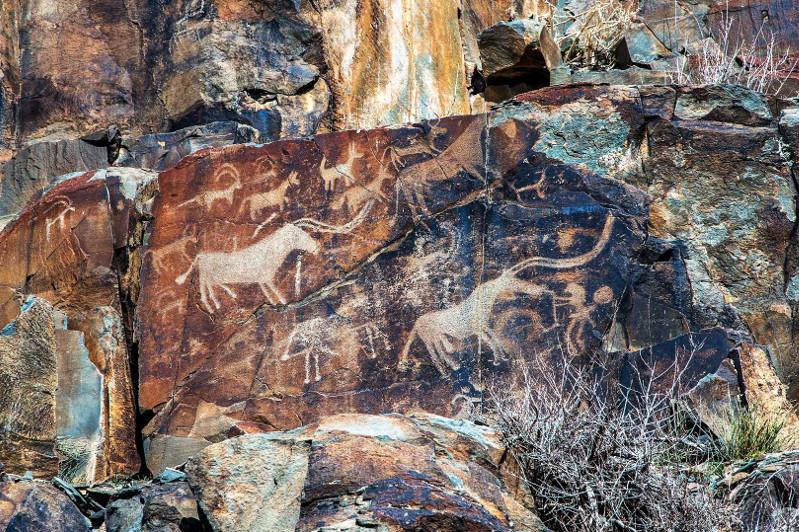

THE GRASSLAND STEPPES stretch away to the horizon in the far south of Kazakhstan. In a landscape blasted with summer heat and winter cold, the shelter and shade of the Tamgaly gorge, about 100 miles northwest of the former Kazakh capital, Almaty, has been a special place for people for millennia. They have left their mark in the form of 5,000 vivid rock carvings, the earliest of which date from the middle of the Bronze Age, 3,500 years ago.

Some of these carvings are hidden, while others’ placement ensures maximum visibility. The petroglyphs stand out in pale contrast to the dark rock revealing myriad drawings: sun deities with rays shining from their heads, warriors on horses, dancing shamans, and herds of animals.

All tell of the different peoples that lived here: Their subjects chart the changes felt through the region from the Bronze Age through the Iron Age to the medieval period, and even much later: Twentieth-century Kazakh shepherds have also left their mark, recording the recent conquerors of the region with depictions of Soviet-era vehicles.

The 'Marked Place'

The Tamgaly gorge is one of several sites in Kazakhstan noted for petroglyphs. (Confusingly, another site rich in petroglyphs farther to the east is named Tamgaly-Tas). The name Tamgaly in Kazakh means “marked” or “painted place,” and—as the evidence of 20th-century carvings by shepherds attests—Tamgaly’s rock art was clearly known by Kazakhs for many centuries.

In 1957 a Soviet team of archaeologists, led by Anna Maksimova, began exploring and documenting the artwork in the area. They started the complex task of sorting the thousands of engravings into groups. Hers and subsequent investigations—most recently those undertaken by Alexey Rogozhinsky in the early 2000s— have dated the forms, analyzing them to discern what such figures meant to the people who created them.

Maksimova’s studies confirmed that Tamgaly had been inhabited, almost without interruption, since circa 1500 B.C., a period of the Middle Bronze Age. Lowering water tables in the steppes had attracted more settlement across the region during this period, and the lush pastures around Tamgaly drew herding communities. Since Maksimova’s first survey of the site, more Bronze Age settlements and several funeral complexes have been uncovered. (The oldest North American rock art may be 14,800 years old.)

Over millennia, earthquakes had split Tamgaly’s sandstone rocks and created flat, smooth surfaces. At some stage, Bronze Age peoples first began to etch petroglyphs into the soft, smooth rock using sharp stones or metal instruments to create pictures in the dark patina on the rock faces.

Shamans and sun gods

The archaeological studies carried out at Tamgaly divide the 3,000 oldest petroglyphs into five groups, clustered mainly on the eastern slopes around a central section of the Tamgaly gorge.

Farthest north is Group I, consisting of 100 carefully hidden engravings of human beings—perhaps shamans, who appeared to have access to the realm of spirits—as well as hunting vignettes and depictions of local wildlife, including wolves. (This ancient cave art may be the world's oldest hunting scene.)

Farther south is Group II, which is made up of more visible engravings and includes depictions of worshippers and shamans, representations of sexual intercourse, and animals such as deer and bulls. Group III consists of 800 engravings, many depicting people engaging in animal-related rituals, especially involving bulls, horses, and cattle.

Group IV, the only cluster on the western side of the gorge, is dominated by a panel depicting human-like figures dancing around a female figure who appears to be giving birth. This grouping is sited on the upper slopes and is clearly visible from the gorge.

Dark and light

Group V, the cluster farthest south, contains some 1,000 petroglyphs. Their organization appears both more complex and deliberate. Ascending a slope, a hierarchy related to altitude becomes evident: The lower section is dominated by depictions of worshippers and shamans. Higher up the slope appear distinctive figures that many believe are sun gods. They have human forms topped by circles with emanating rays. Higher still, a panel shows more of these solar deities with a chariot. These 3,000 petroglyphs in Tamgaly’s five gorge-based groups have been dated to the Middle Bronze Age (1500-1200 B.C.) and the Late Bronze Age (1200-900 B.C.). There are 26 surviving sun-head figures at Tamgaly, leading scholars to suggest that this sun god was especially revered here. (Isis, ancient Egypt's mother goddess, was often depicted wearing a sun disk on her head.)

Another figure that predominates in the Bronze Age engravings is the bull, which like the sun-god forms, can be seen at other petroglyph sites in the region. Only at Tamgaly, however, are there examples of sun gods interacting with the bulls. In a Group IV petroglyph, a solar deity stands on a bull. Scholars have interpreted this arrangement to be a dualist idea of the darkness of the black bull in opposition to the light emitted in rays from the sun-head.

Other interactions are represented throughout the petroglyphs at Tamgaly: Humans relate with animals, such as horses, by riding or mastering them. In other scenes, shaman figures reach out to the spirit world by donning animal skins. The panel scene in Group IV in which people dance around a woman giving birth is believed to represent a ritual dance carried out during a birth in order to obtain protection from the gods.

Artistic expressions

Settlement in the area began to decline by the end of the Bronze Age, but researchers believe that the area was still inhabited. The people who lived there during this period left their mark. There are more than 2,000 additional petroglyphs that date to this transitional period. (A study links ancient cave drawings to early human language.)

Among these petroglyphs that date to the Early Iron Age (800-300 B.C.) are more detailed depictions of animals, such as camels and deer with branching horns. These pieces were carved when the area was dominated by the Saka, an Iranian steppe people. The human figures are more simply rendered resembling a child’s stick figures drawings. Later, the region was settled by Turkic tribes, and much later engravings (A.D. 700-1300) depict scenes from aristocratic Turkic life: knights with banners and hunting scenes. Many of the Turkic figures are superimposed over older work.

The many time periods encompassed by the site present a challenge to today’s scholars, who still have much to unravel. Researchers Alexey Rogozhinsky and Renato Sala, who carried out extensive surveys after Tamgaly was designated a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2004, are making finer distinctions within the Bronze Age groups, noting early and late styles.

They and other scholars of the wonders of Tamgaly stress that the engravings cannot be seen as isolated images. They must be studied as parts of a whole, whose overall meaning, and relation to the landscape, has yet to be fully decoded.

BY ANTONIO RATTI

Источник: nationalgeographic.com

- Created on .